A simpler way to understand syntax

For decades, Professor Ted Gibson has taught the meaning of language to first-year graduate students in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. A new book, Gibson's first, brings together his years of teaching and research to detail the rules of how words combine.

“I actually don't think the form for grammar rules is that complicated,” Gibson says. “I've taught it in a very simple way for many years, but I've never written it all down in one place.”

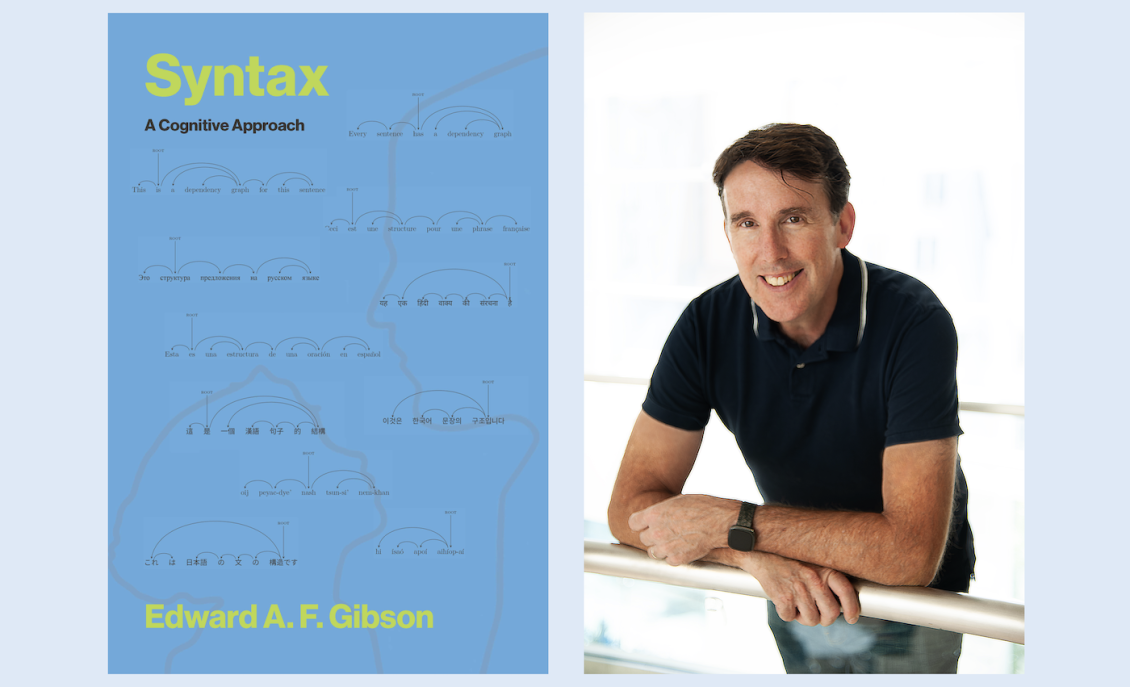

"Syntax: A Cognitive Approach," released by MIT Press on December 16, lays out the grammar of a language from the perspective of a cognitive scientist, outlining the components of language structure and the model of syntax that Gibson advocates: dependency grammar.

It was his wife and research collaborator, Associate Professor Brain and Cognitive Sciences and McGovern Institute Investigator Ev Fedorenko, who encouraged him to put pen to paper.

"She suggested a paper," Gibson says. "It turned into a book."

Gibson took some time to discuss his new book:

Where did the process for this book begin?

I think it started with my teaching. Course 9.012, which I teach with Josh Tenenbaum and Pawan Sinha, divides language into three components: sound, structure, and meaning. I work on the structure and meaning parts of language: words and how they get put together. That's called syntax.

I've spent a lot of time over the last 30 years trying to understand the compositional rules of syntax, and even though there are many grammar rules in any language, I actually don't think the form for grammar rules is that complicated. I've taught it in a very simple way for many years, but I've never written it all down in one place. My wife, Ev, is a longtime collaborator, and she suggested I write a paper. It turned into a book.

How do you like to explain syntax?

For any sentence, for any utterance in any human language, there's always going to be a word that serves as the head of that sentence, and every other other word will somehow depend on that headword, maybe as an immediate dependent, or further away, through some other dependent words. This is called dependency grammar; it means there's a root word in each sentence, and dependents of that root, on down, for all the words in the sentence, form a simple tree structure. I have cognitive reasons to suggest that this model is correct, but it isn't my model; it was first proposed in the 1950s. I adopted it because it aligns with human cognitive phenomena.

That very simple framework gives you the following observation: that longer distance connections between words are harder to produce and understand than shorter distance ones. This is because of limitations in human memory. The closer the words are together, the easier it is for me to produce them in a sentence, and the easier it is for you to understand them. If they're far apart, then it's a complicated memory problem to produce and understand them.

This gives rise to a cool observation: Languages optimize their rules in order to keep the words close together. We can have very different orders of the same elements across languages, such as the difference in word orders for English versus Japanese, where the order of the words in the English sentence “Mary eats an apple” is “Mary apple eats” in Japanese. But then the ordering rules in English and Japanese are aligned within themselves in order to minimize dependency lengths on average for the language.

How does the book challenge some longstanding ideas in the field of linguistics?

In 1957, a book called “Syntactic Structures” by Noam Chomsky was published. It is a wonderful book that provides mathematical approaches to describe what human language is. It is very influential in the field of linguistics, and for good reason.

One of the key components of the theory that Chomsky proposed was the “transformation,” such that words and phrases can move from a deep structure to the structure that we produce. He thought it was self-evident from examples in English that transformations must be part of a human language. But then this concept of transformations eventually led him to conclude that grammar is unlearnable, that it has to be built into the human mind.

In my view of grammar, there are no transformations. Instead, there are just two different versions of some words, or they can be underspecified for their grammar usage. The different usages may be related in meaning, and they can point to a similar meaning, but they have different dependency structures.

I think the advent of large language models suggests that language is learnable and that syntax isn't as complicated as we used to think it was, because LLMs are successful at producing language. A large language model is almost the same as an adult speaker of a language in what it can produce. There are subtle ways in which they differ, but on the surface, they look the same in many ways, which suggests that these models do very well with learning language, even with human-like quantities of data.

I get pushback from some people who say, well, researchers can still use transformations to account for some phenomena. My reaction is: Unless you can show me that transformations are necessary, then I don’t think we need them.

This book is open access. Why did you decide to have it published that way?

I am all for free knowledge for everyone. I am one of the editors of “Open Mind,” a journal established several years ago that is completely free and open access. I felt my book should be the same way, and MIT Press is a fantastic University Press that is non-profit and supportive of open access publishing. It means I make less money, but it also means it can reach more people. For me, it is really about trying to get the information out there. I want more people to read it, to learn things. I think that's how science is supposed to be.