Microscope system sharpens scientists’ view of neural circuit connections

The brain’s ability to learn comes from “plasticity,” in which neurons constantly edit and remodel the tiny connections called synapses that they make with other neurons to form circuits. To study plasticity, neuroscientists seek to track it at high resolution across whole cells, but plasticity doesn’t wait for slow microscopes to keep pace, and brain tissue is notorious for scattering light and making images fuzzy. In an open access paper in Scientific Reports, a collaboration of MIT engineers and neuroscientists describes a new microscopy system designed for fast, clear, and frequent imaging of the living brain.

The system, called “multiline orthogonal scanning temporal focusing” (mosTF), works by scanning brain tissue with lines of light in perpendicular directions. As with other live brain imaging systems that rely on “two-photon microscopy,” this scanning light “excites” photon emission from brain cells that have been engineered to fluoresce when stimulated. The new system proved in the team’s tests to be eight times faster than a two-photon scope that goes point by point, and proved to have a four-fold better signal-to-background ratio (a measure of the resulting image clarity) than a two-photon system that just scans in one direction.

“Tracking rapid changes in circuit structure in the context of the living brain remains a challenge,” says co-author Elly Nedivi, the William R. (1964) and Linda R. Young Professor of Neuroscience in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and MIT’s departments of Biology and Brain and Cognitive Sciences. “While two-photon microscopy is the only method that allows high-resolution visualization of synapses deep in scattering tissue, such as the brain, the required point-by-point scanning is mechanically slow. The mosTF system significantly reduces scan time without sacrificing resolution.”

Scanning a whole line of a sample is inherently faster than just scanning one point at a time, but it kicks up a lot of scattering. To manage that scattering, some scope systems just discard scattered photons as noise, but then they are lost, says lead author Yi Xue SM ’15, PhD ’19, an assistant professor at the University of California at Davis and a former graduate student in the lab of corresponding author Peter T.C. So, professor of mechanical engineering and biological engineering at MIT. Newer single-line and the mosTF systems produce a stronger signal (thereby resolving smaller and fainter features of stimulated neurons) by algorithmically reassigning scattered photons back to their origin. In a two-dimensional image, that process is better accomplished by using the information produced by a two-dimensional, perpendicular-direction system such as mosTF, than by a one-dimensional, single-direction system, Xue says.

“Our excitation light is a line, rather than a point — more like a light tube than a light bulb — but the reconstruction process can only reassign photons to the excitation line and cannot handle scattering within the line,” Xue explains. “Therefore, scattering correction is only performed along one dimension for a 2D image. To correct scattering in both dimensions, we need to scan the sample and correct scattering along the other dimension as well, resulting in an orthogonal scanning strategy.”

In the study the team tested their system head-to-head against a point-by-point scope (a two-photon laser scanning microscope — TPLSM) and a line-scanning temporal focusing microscope (lineTF). They imaged fluorescent beads through water and through a lipid-infused solution that better simulates the kind of scattering that arises in biological tissue. In the lipid solution, mosTF produced images with a 36-times better signal-to-background ratio than lineTF.

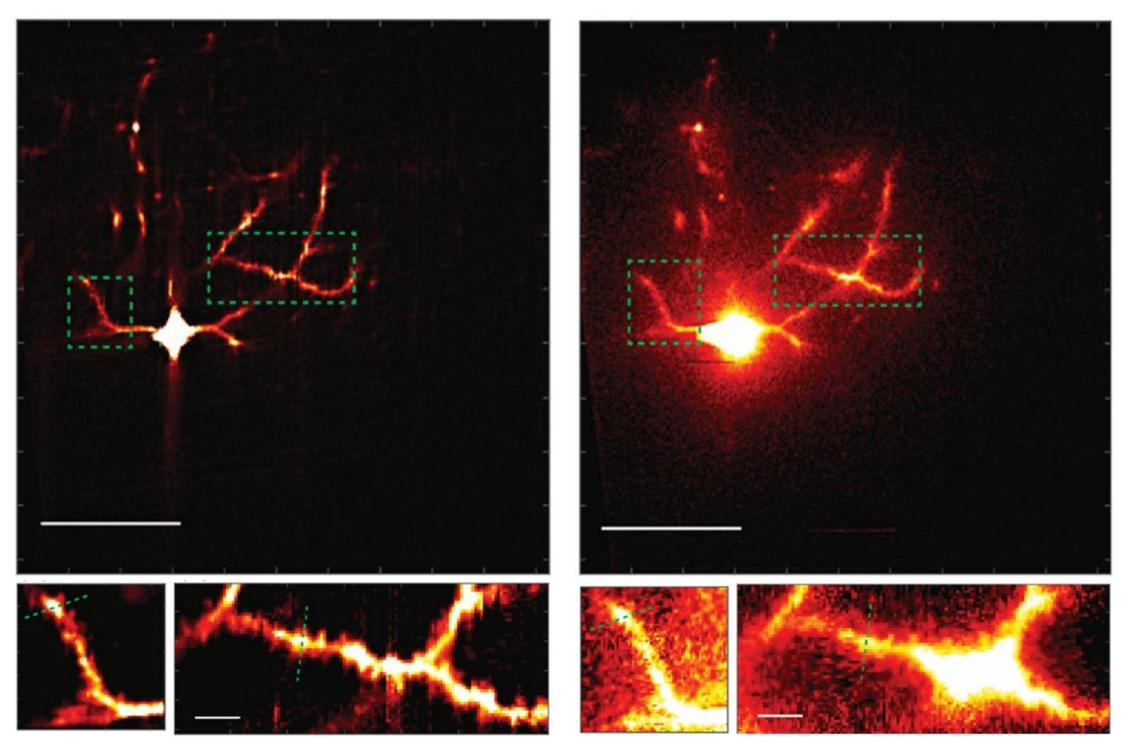

For a more definitive proof, Xue worked with Josiah Boivin in the Nedivi lab to image neurons in the brain of a live, anesthetized mouse, using mosTF. Even in this much more complex environment, where the pulsations of blood vessels and the movement of breathing provide additional confounds, the mosTF scope still achieved a four-fold better signal-to-background ratio. Importantly, it was able to reveal the features where many synapses dwell: the spines that protrude along the vine-like processes, or dendrites, that grow out of the neuron cell body. Monitoring plasticity requires being able to watch those spines grow, shrink, come, and go across the entire cell, Nedivi says.

“Our continued collaboration with the So lab and their expertise with microscope development has enabled in vivo studies that are unapproachable using conventional, out-of-the-box two-photon microscopes,” she adds.

So says he is already planning further improvements to the technology.

“We’re continuing to work toward the goal of developing even more efficient microscopes to look at plasticity even more efficiently,” he says. “The speed of mosTF is still limited by needing to use high-sensitivity, low-noise cameras that are often slow. We are now working on a next-generation system with new type of detectors such as hybrid photomultiplier or avalanche photodiode arrays that are both sensitive and fast.”

In addition to Xue, So, Boivin, and Nedivi, the paper’s other authors are Dushan Wadduwage and Jong Kang Park.

The National Institutes of Health, Hamamatsu Corp., Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology, Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology Center, Biosystems and Micromechanics, The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, The JPB Foundation, and The Center for Advanced Imaging at Harvard University provided support for the research.