In Memory: Richard J. Wurtman

Training and early career. Dr. Richard J. Wurtman was born in Philadelphia and earned his undergraduate degree at the University of Pennsylvania. As a Harvard Medical School student, he became captivated by research and began publishing research on the pineal gland and its functions. After receiving an MD degree in 1960, he trained in a residency program at the Massachusetts General Hospital, but research was his calling. Two years later, he joined the pioneering laboratory of Dr. Julius Axelrod (later a Nobel laureate) at the National Institutes of Health. In this heady environment, he enthusiastically embraced research on neurotransmitters, their vital role in brain communication, and how therapeutic drugs affect their function. This six-year productive collaboration led to 54 publications with “Julie” Axelrod! His creativity, intellect, energy and enthusiasm for collaborative research catapulted him to the next phase of his career, where he remained for the duration of his professional life.

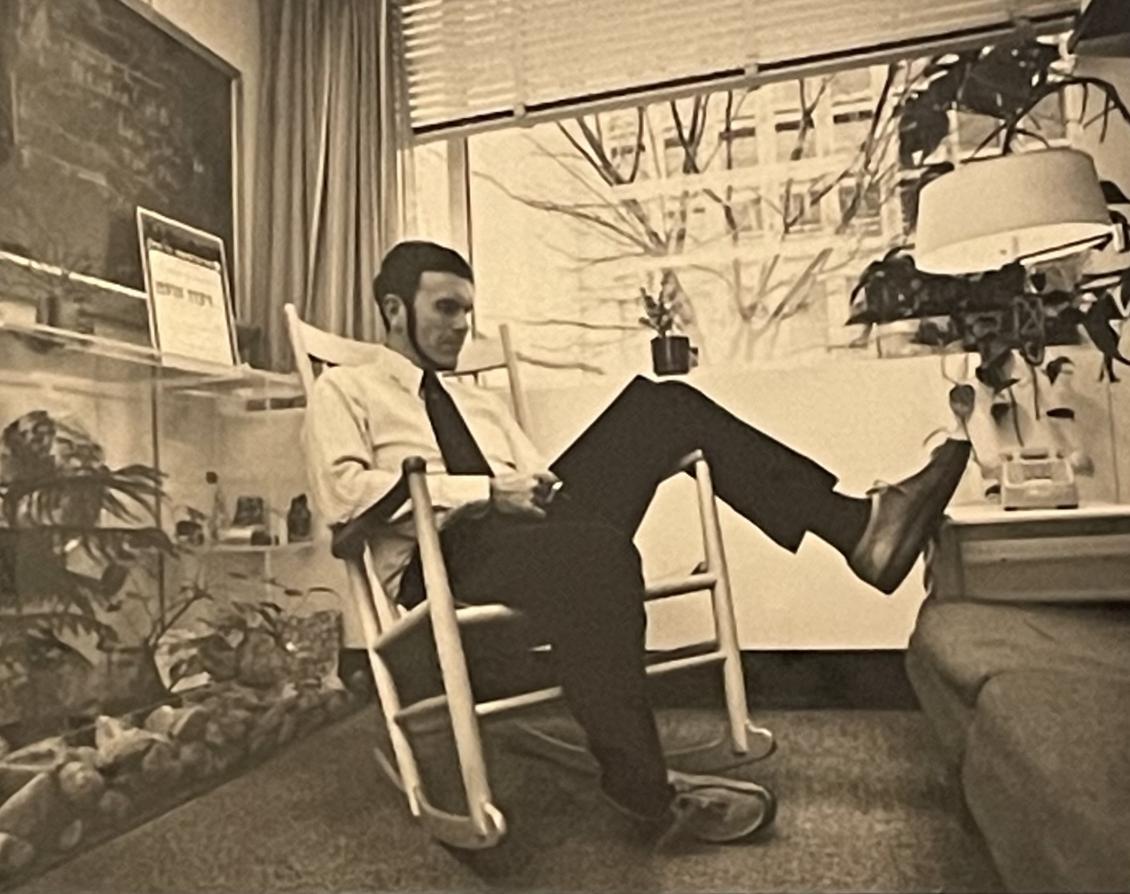

MIT faculty. By 1970, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had recruited him for a faculty appointment in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science. In the 1980s, the university formed a Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences in recognition of the consequential value of neuroscience research. In this professional home, Dr. Wurtman was honored with an endowed chair, the first Cecil H. Green Distinguished Professor at MIT, and other titles as Professor of Neuroscience in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and Professor of Neuropharmacology in the Harvard–MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology.

Research. Dick’s inquisitiveness and hunger for discovery was never constrained by the more common approach of “theme and variations” experiments. He structured his research program on a well-defined strategy: to seek a previously unsuspected control mechanism of brain chemistry in preclinical experiments, confirm that this mechanism functioned in the human brain, investigate whether a pathophysiological state is linked to this mechanism, and then develop and test potential treatments based on these discoveries. Much of his work involved pursuing new functions of existing hormones or neurotransmitters and expanding on practical applications of this discovery. His early encounter with Dr. Hamish Munro in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science sparked intense curiosity of whether food and nutrients affect brain function, thereby establishing the foundation for medical products. Among his early discoveries was identifying melatonin as a hormone secreted at nighttime that promoted sleep. Approximately 3 million people in the United States who take melatonin as a sleeping aid are using a product based on research in Dick Wurtman’s lab. The topics of his research and discoveries ranged far and wide. His research demonstrated that certain nutrients could drive neurotransmitter precursor levels in the brain or enhance the molecular composition of brain membranes, which are critical for efficient brain signaling. Candidate therapeutics based on his translational research, including those attributable to his wife and longtime innovative collaborator, Dr. Judy Wurtman, ranged from biogenic amines to treat obesity, fluoxetine to treat premenstrual syndrome, and others to treat strokes and brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, and a protein/carbohydrate mixture to enhance the efficacy of L-dopa in treating Parkinson's. Dr. Wurtman co-founded several companies to translate his discoveries into practice.

Dick Wurtman’s legacy resides within the careers of hundreds of trainees and collaborators he launched or enhanced, the 1,000+ published research articles, his numerous patent awards and people who benefited from his therapeutic approaches. Yet, these quantitative metrics, legacies of research and mentoring do not illustrate the charitable qualities of this remarkable man.

A personal story. My own history with Dick Wurtman, beginning more than 50 years ago, is a testimony to his humanistic nature. Following a productive period as a newly minted post-doctoral fellow, I was expecting my first child. My inner voice urged me to stay at home full-time after the birth, during the early developmental years. To be wholly separated from science, my colleagues warned, would be committing “research suicide.” After a three-year hiatus was over and just prior to meeting Dick, I initiated a search for a research position in the Boston region, by applying to two labs led by quality scientists. During each interview and after discussing research projects, the discussion headed in a different direction. I asked whether I could work part-time (2.5 to 3 days a week) and pledged to work late nights and weekends to compensate for this arrangement. I felt that 5 to 6 long days away from my daughter would be a difficult adjustment for her, as my husband Peter was a surgical resident on call and sleepless every second night and every second weekend. He had an untenable schedule to rely on for childcare. Without hesitation, both stated in almost identical terms that they would welcome me into their labs for full-time research, but children are of zero priority for a scientist. They refused to accommodate to or consider any requests for my child’s well-being. I had to choose.

After these interviews, I approached Dick Wurtman in a corridor after a neuroscience seminar I attended; he was working in the field of my dreams—neurotransmitters. With now deeper insecurities than even before, I was certain that he too would turn down my request for part-time research and question my 3-year hiatus. With very low expectations, I entered his office a few weeks later for an interview. But Dick Wurtman was different. I started off by describing my research, and he interrupted me; it wasn’t necessary because he had already contacted my former mentors. After a discussion of ongoing research in his lab, I slowly, hesitatingly, asked if it was possible to work part- time because I could not leave my child 5 to 6 long days a week. Without hesitation, he bellowed: “Of course! My wife Judy also has these conflicts between work and being a mother; I completely understand the anguish you’re going through, especially with a first-born. Make your own hours, come and go, as you need. As long as you set goals and are productive, I don’t care what hours you work.” I was stunned, elated and drove home feeling optimistic for the first time in months, years. For experimental protocols requiring 12 hours or longer, I would drive home and back to the lab with my little daughter after the babysitter left, making a bed of comforters for her in a clean area. At 2 or 3 a.m., I would gather my sleeping child enveloped by blankets and drive home. (Fifteen years later, after delivering my daughter to her MIT dorm, she would be sleeping once again on the MIT campus, but this time in a real bed). Soon we had a Nature publication, the manuscript submitted within three hours of Dick’s editing my draft on a Sunday afternoon.

Dick encouraged me to present my data at my first international meeting in Sardinia, Italy. During the flight overseas, and for decades later, I reflected on my good fortune in encountering Dick Wurtman. In those two precious years in his lab, my goal of a career in neuroscience research was revitalized. When I relocated to Toronto, he called several times, encouraging my ongoing career in Canada. Throughout this period, I witnessed his deep intellect, boundless energy, enthusiasm, optimism and generosity toward trainees, qualities that helped to sustain me during crests and troughs encountered in the adventures of a scientific career. Dr. Richard Wurtman was a creative, brilliant scientist, a mentor, a devoted husband to his beloved wife, Dr. Judy Wurtman, and loving father and grandfather to his children and grandchildren. Above all, he was righteous.

Bertha K. Madras, PhD, Professor of Psychobiology,

McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School