For bilinguals, the dominant language doesn't always dominate

In which language do bilingual speakers more easily select words to speak and write? Contemporary cognitive models offer a seemingly self-evident answer: the speaker's dominant language. Ask bilingual speakers, however, and they may beg to differ. According to a new MIT study, they have good reasons to do so. The study shows that bilingual speakers more easily select words in topics they are particularly proficient in, even when these words are not in their dominant language.

"Think of a foreign student at an American university who has an easier time coming up with academic jargon in English rather than in her native tongue," says Saima Malik-Moraleda, a PhD student in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences who is the lead author of the study. "The results show that we need a better working definition of proficiency. The current models rely on a vague notion of 'overall proficiency,' which doesn't take into consideration specialized proficiency in specific word categories. But for many bilingual speakers, this is a common experience."

Alongside Malik-Moraleda, the paper's second author is Manuel Roca, a Tsimane' translator from the Centro Boliviano de Dessarrollo Socio Integral in San Borja, Bolivia. The senior author is Edward (Ted) Gibson from MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

Researchers developed in recent years two central cognitive models to explain word access by bilinguals. While these models offer two different mechanisms to explain bilingual word selection, they both assume that speakers have easier access to all words in their dominant language compared to the non-dominant language. Overall proficiency is the name of the game.

However, overall proficiency doesn't account for differing proficiency levels across a given language. In fact, recent studies indicate that the frequency of exposure to certain words affects the ability to access them. The more frequent the exposure to a particular word, the easier it is to select.

The question therefore arises: does a bilingual speaker's specialized proficiency in specific word categories – music, neuroscience, historical figures, and so on – provide easier access to these words, even if spoken in the non-dominant language?

Conducting such comparative research is easier said than done. According to Malik-Moraleda, the similarities between the languages and cultures commonly investigated in such studies don't always allow for effective comparisons.

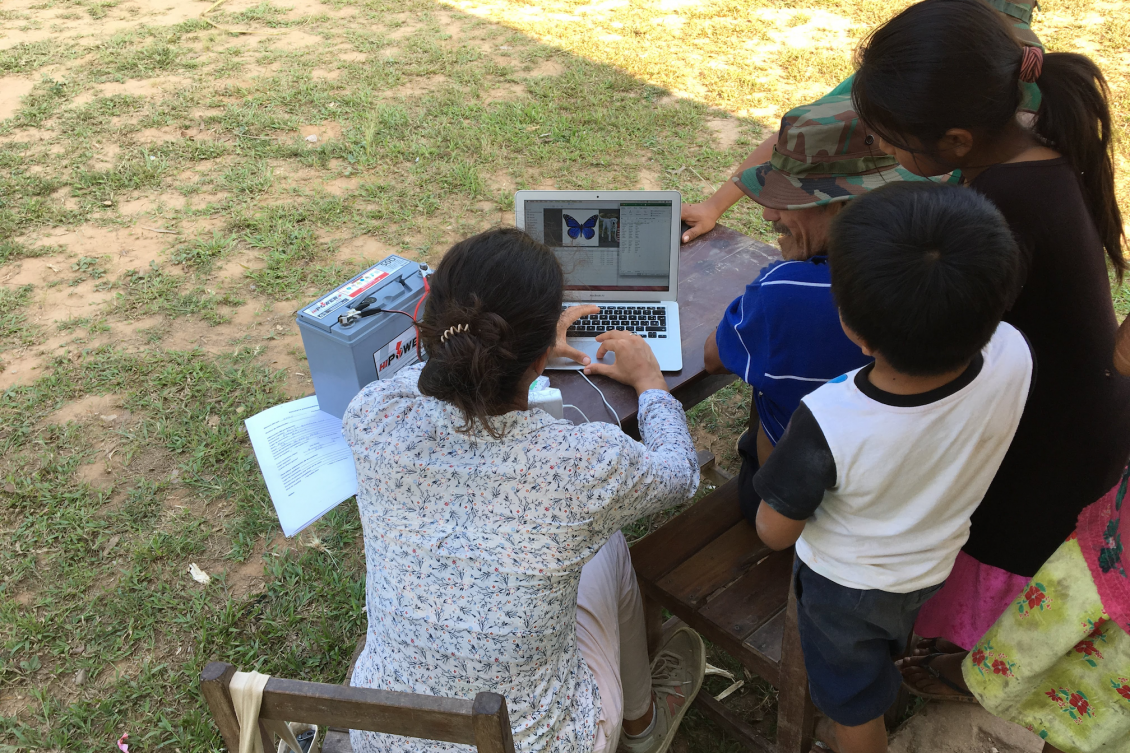

Malik-Moraleda overcame this challenge by working with a group of Tsimane' – farmer foragers living in the Bolivian Amazon rainforest. These villagers lived for some time in nearby Spanish-speaking Bolivian communities, making them bilingual speakers of both Tsimane' and Spanish.

Malik-Moraleda sought to test the proficiency of the villagers in their color vocabulary. While Tsimane' speakers use mainly three colors consistently in their daily speech – black (tsincus), white (jaibes) and red (jaines) – Bolivian Spanish speakers commonly use eight more color words: verde (green), amarillo (yellow), celeste (light blue), azul (dark blue), rosado (pink), anaranjado (orange), violeta (purple), and gris (grey). These color words are usually not invoked in the Tsimane' native language.

Malik-Moraleda hypothesized that the villager would conjure these eight color words more easily in Spanish than in Tsimane', despite Tsimane' being their mother language. If this were the case, she could show that specialized proficiency outweighs overall proficiency in determining the ease of access to words.

Twenty two Tsimane’-Spanish bilingual speakers participated in the study. The researchers asked them to identify colors in a set of pictures as fast as they could. As Malik-Moraleda predicted, the participants could name the eight colors in Spanish, the language in which these names are more commonly used, faster than in their native language. Moreover, there was no difference in their ability to name the colors black, white, and red, which are just as prevalent in their language.

Both results show that specialized proficiency – in this case, color vocabulary in Spanish – outweighs the importance of overall proficiency – in this case, in Tsimane'. However, it remains to be seen in further studies if general proficiency in the dominant languages still plays any role in such cases.